“One memory in particular has preoccupied me all morning – or rather, a fragment of a memory, a moment that has for some reason remained with me vividly through the years. It is a recollection of standing alone in the back corridor before the closed door of Miss Kenton’s parlour; I was not actually facing the door, but standing with my person half turned towards it, transfixed by indecision as to whether or not I should knock; for at that moment, as I recall, I had been struck by the conviction that behind that very door, just a few yards from me, Miss Kenton was in fact crying.”

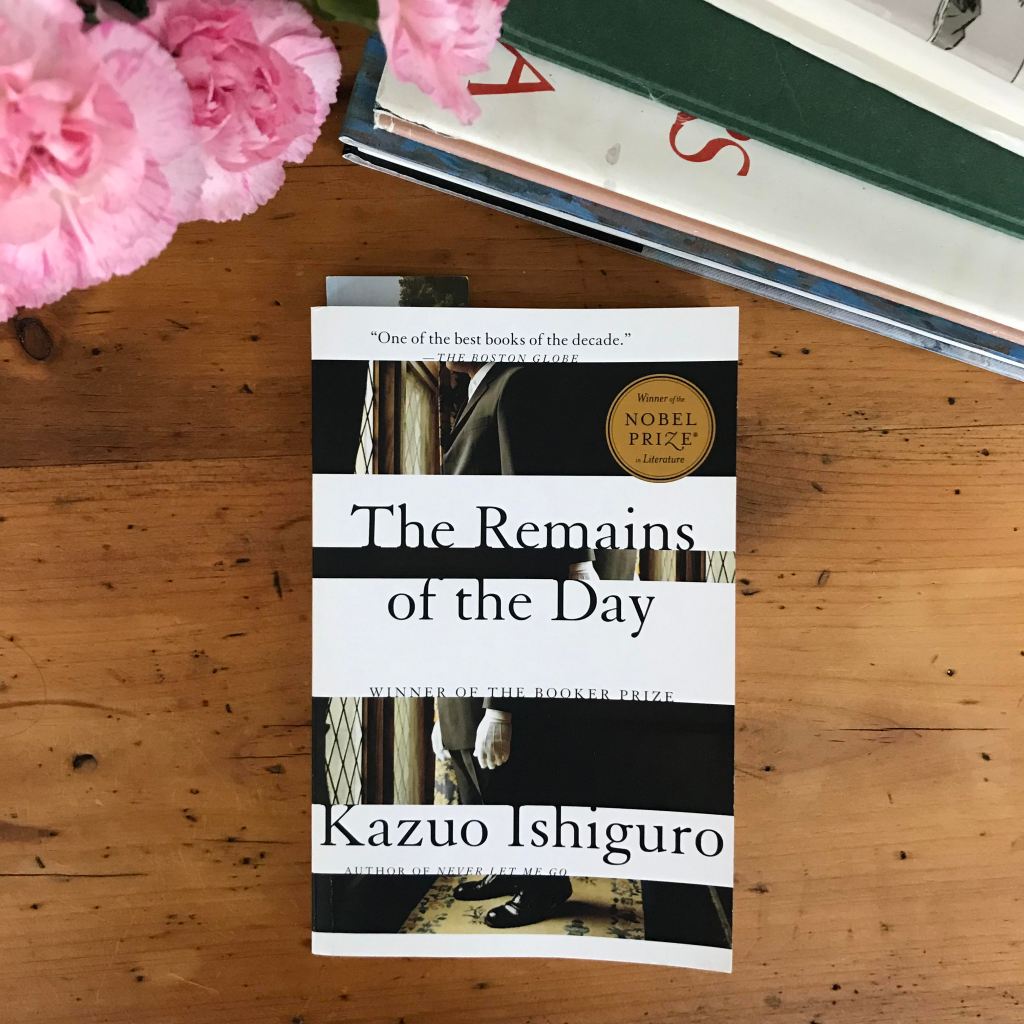

from Kazuo Ishiguro’s The Remains of the Day

It is July 1956 at Darlington Hall and after careful consideration, Stevens, the ever loyal butler, accepts his new employer’s offer. He is to borrow Mr Farraday’s Ford and embark on a drive through the English countryside while the house sits empty during his employer’s leave to America. What follows is a novel set over the course of six days, divided by mornings, afternoons, and evenings in various parts of England, and marked by chance encounters that reveal both Stevens’ character and the country’s new postwar reality. While the journey begins in Salisbury and ends in Weymouth, the narrative stretches through Stevens’ decades of service and carefully retraces his memories serving Lord Darlington, particularly during the years leading up to the Second World War.

Kazuo Ishiguro introduces us to a protagonist who is delicate with his words and handles his memories as if they were fragile pieces from a rare and expensive collection. We come to know Stevens as a man dedicated to his profession and to his employer; a man with strict principles and ideals; and a man defined by the importance of his role and by the status of the men he served.

As Stevens drives through the English countryside, he recalls the events and conversations that took place at Darlington Hall that once reassured him of the importance of his career and of Lord Darlington’s status as a ‘great gentleman’. But as Stevens retraces these memories, we begin to unveil the questionable role and position Darlington Hall held in prewar England, which was both moulded and sustained by Lord Darlington himself. As Stevens unravels these events, he becomes doubtful of the justification he has held of his own career and of his employer, forcing him to look more closely and more critically at the decades he has spent at Darlington Hall.

In Stevens, Ishiguro has crafted one of the most unique characters and distinct voices I have yet to read. While The Remains of the Day is a novel about postwar England and about the unsteady status of country homes, it is also a novel about remembering and about the revealing and at times heartbreaking realizations that accompany moments of recollection. Centred around one man’s memories, we witness a character in solitude, recognizing and coming to terms with relinquished opportunities, actions not taken, and words not said. As I read The Remains of the Day I couldn’t help thinking that I was reading a classic work of fiction that so perfectly portrays what a novel is capable of. I highly recommend this novel and look forward to reading it again one day, but if you’ve already read and enjoyed this book, I would suggest Graham Swift’s Mothering Sunday—a short work I would love to reread alongside Ishiguro’s novel!

Leave a comment